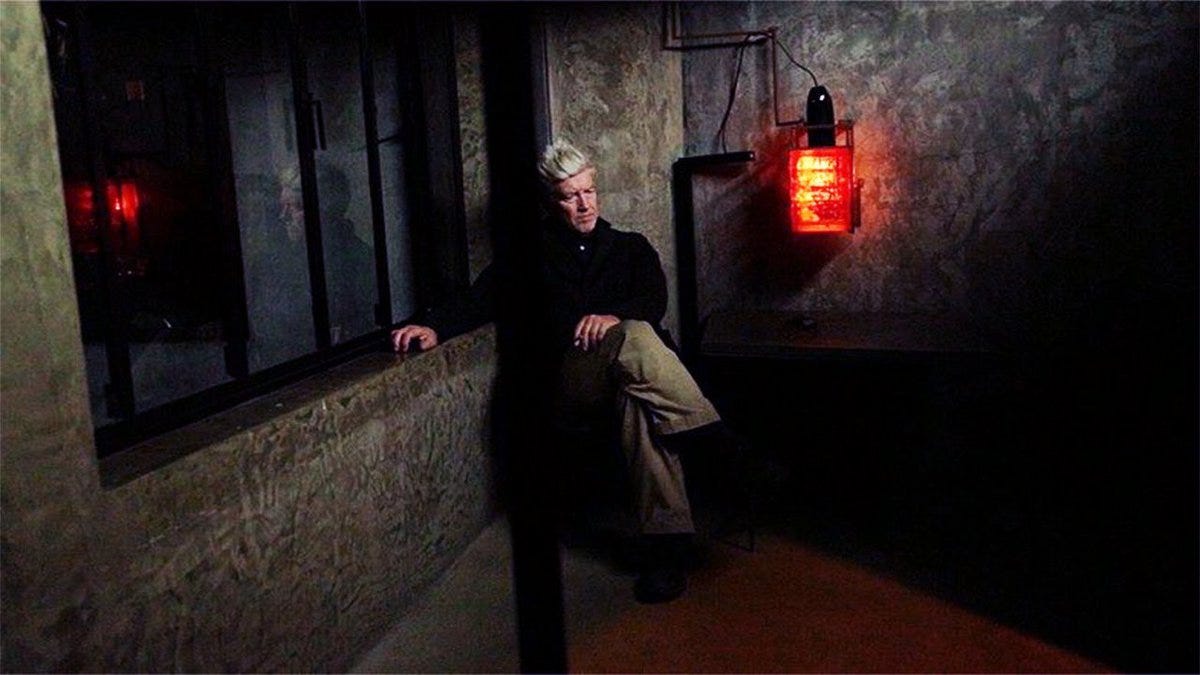

David Lynch was born in Missoula, Montana one year after the invention of the atomic bomb. In the documentary David Lynch: The Art Life, he describes a childhood passed with long days playing outdoors with the neighborhood kids. His mother didn’t give him coloring books, sensing that they would restrict his precocious creativity. To the extent that his death has been mourned as the closing of an epoch in American art and culture, I believe this has to do with the sense that Lynch himself was anachronistic. He was an artist of the twentieth century, and availed himself of its tools – the latest film cameras, electronic recording equipment, eventually digital video – but his creativity sprang from somewhere premodern. When machines appear in his work they carry foreboding and tension. The films are full of silent-era lighting and visual effects: strobe lights and lightning flashes, flames, smoke and steam.

In the latter decades of his career, his legacy as an iconic artist seemed secure. This had not a little to do with his struggle to finance new filmmaking work. During his most prolific period as a director in the ‘80s and ‘90s, when he shocked and fascinated audiences with Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks, he experienced a constant push-pull of critical adulation and hostility toward his true intentions. David Foster Wallace wrote pages and pages trying to sort through his suspicion toward the work, seeing Lynch as an avatar of the era’s superficial cool that belied a slick cruelty. After the ‘90s, it was easier to see a work like Mulholland Drive for the accomplishment it was. And then, for the most part, to simply appreciate Lynch as an artist of another time. Inland Empire, to this day, has been greeted with respectful befuddlement.

When we got Twin Peaks: The Return in the summer of 2017, part of the spell of giddy excitement that spread over that whole year – in its anticipation, the experience itself and its aftermath – was the sense that it had slipped through from another place. It did not make sense for the Hollywood of the twenty-first century to be financing eighteen hours of new Lynch material, yet the streaming era’s gold rush to dust off old IP and resurrect abandoned projects had allowed it to happen. When the new episodes unfolded, we found that this sense of wrongness – that this should not be happening – was on Lynch’s mind as well. This was one of the things to admire or to resent about the new series: its prickly attitude toward the idea of continuation, or the possibility of resolution. At times, as with Big Ed and Norma, Lynch and his collaborator Mark Frost seemed to find joy in revisiting these characters. With others, like Audrey, Cooper, and Laura Palmer herself, the ambivalence – perhaps what Wallace had identified as cruelty – seemed more pronounced.

Personally, I have always tried to protect the parts of Lynch that put me off. Part of this, I think, was a necessary critical posture to avoid softening the edges of his work, and to try to keep his career alive. His ascension to something like cinephile grandpa meme status, on par with Scorsese or Herzog, seemed inseparable from his marginalization in Hollywood. (This was not entirely imposed on him from without — his sense of humor and propensity for gnomic non-statements made him a fount of good soundbites.) It was easier for the industry to appreciate him – to pre-mourn him, for example, by giving him an Honorary Academy Award – rather than pay him the respect of continuing to finance his work. You can see this in the insipid remembrance posted by Netflix Co-CEO Ted Sarandos this week, patting himself on the back for having been associated with Lynch without actually producing any of his ambitious unrealized projects.

Why this reluctance on the industry’s behalf? Why were streamers only interested in a continuation of what had worked before? That Lynch’s work was noncommercial, stridently so, seems too easy an answer. He was either the mainstream’s most experimental filmmaker or the world’s most popular avant-garde filmmaker, depending how you look at it. There would have been an audience for anything he made. Honestly, I don’t think Hollywood had much to do with the successes in Lynch’s career. You can see his frustrations with conforming to The Return’s demanding shooting schedule — precipitated by budget negotiations that caused him at one point to announce his departure from the project — in a candid video clip. He was not interested in working the way the industry wanted him to, and it had been that way for decades, not only with the streamers. He seemed to prefer painting and music, or collaborating on a memoir, Room to Dream, to pursuing new film projects that would require a compromised approach. The current grieving for Lynch as a veteran director who once thrived in Hollywood and was pushed out the door in his twilight years is another case of trying to fit him into a simplistic frame. He didn’t fit into the current Hollywood because he never had.

I’ve never considered Lynch a political filmmaker, although since he has been interpreted through every lens imaginable, there are surely those critics who would mount strong arguments in favor of this reading. Those premodern elements in his work, rather, have always suggested an interest in power – natural, environmental, primal forces, which man harnesses for good and evil. In the eighth episode of The Return he made his most explicit statement about the nature of evil, that it was summoned into the world by man’s quest for power, specifically in the invention of the atom bomb. Lynch was not a cinephile filmmaker, although he had his touchstones, The Wizard of Oz and It’s a Wonderful Life among them — movies about going to sleep and waking up and what happens in between. Crucially, these stories also came from artists influenced not by other stories but by earth-shaking calamities: the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl, the World Wars.

Lynch was interested in gendered power, in violence inflicted on women. In The Return, he suggests that the demon BOB, a rapist and murderer of women who feeds on pain and suffering, was one of the forces unleashed by the Trinity Test. There’s maybe a logical gap there, since misogyny predates the bomb, but these evils – the industrialized murder represented by the atomic blast and the localized, personal crimes of murder and rape – are central to his work. What has always set Lynch apart for me was the seriousness with which he treated these subjects (not always straightforwardly – he experimented boldly with tone, especially in the waves of theatrical grief that flood through the pilot of Twin Peaks, crossing over into camp and back again). A key scene in his filmography is the climactic murder in “Lonely Souls”, an agonizing, drawn-out strangulation that forces the audience to sit with their horror. This is what it means to take a life.

I don’t know how many other people, at least those familiar with the piece, were in the mood to revisit pd187’s paranoid reading of Lost Highway this week. It may seem disrespectful, even irresponsible to air these speculations in a time of mourning. To me this essay is the mirror image of the moral seriousness I find in “Lonely Souls”. Whether you take them seriously or literally, I think the paranoid critic pays a compliment to their subject; pd suggests that Lynch has so squarely put his finger on the reality of evil that the work suggests a more intimate familiarity with violence than his avuncular, softened reputation can accommodate. The upshot of the skeptic’s argument against Lynch (a minority opinion by now) is that his cinema synecdochized something about America. If American art depends on the abjection and suffering of women, so did Lynch’s cinema. But he saw it, and drew it, more clearly than anyone else had.

The mourning for Lynch interlaces with the mourning for Los Angeles this week, as the Palisades and Eaton fires inch toward containment. It seems likely the air quality had something to do with Lynch’s death, already attributed to his emphysema diagnosis last year. His passing has been made to stand in for what is being lost – the industry as it was, the movies as we knew them, the artistic legacy of the long twentieth century. If we want another artist like David Lynch, the bittersweet news is the film industry as it existed need not be reproduced as it was. The conditions are already manifesting themselves anew. Lynch was born into a world informed by great civilizational trauma, but shielded by the prosperity of the American postwar era. His life’s work was to peel back that prosperity, and draw a picture of what he found underneath. As we find ourselves confronting another time of upheaval, disaster, and widespread suffering, we might honor the artists who are leaving us by looking more clearly at the world they showed us – and make some shelter for each other, for everyone who needs a room to dream.