The Rescuers

Chasing runaways in Mad Men, Ross Macdonald, and Richard Yates

Revisiting Mad Men this summer for the first time in several years, I was curious to find how the show would feel after some time and distance. To friends who haven’t seen it, I usually half-joke that it’s best experienced when you are deeply unhappy. Much of the show’s drama comes from the idea of work as a component of personal identity, a theme I thought a lot about during my depressed late twenties. I spent more time on this rewatch looking at the shifts in clothing and style. Reaching for supplementary reading, I was reminded that some of the most detailed criticism of the show focused narrowly on the characters’ wardrobe; in part, it’s a story of costume changes.

People are always running away from something in Mad Men. The central character steals a dead man’s identity in order to escape his punishing childhood, and enters the 1960s as a figure of enlaced prosperity, mystery and desire. The rapid cultural shifts of the decade present all the characters with opportunities for reinvention, to abandon an old life and obligations and try on a new self. Although the booming counterculture allows Don and his rich colleagues to try aging themselves down, to varying degrees of success, throughout the series they inevitably come into conflict with the younger generation. Their children, as well as their younger industry peers, see the advantages of shedding old skin and decide to try it themselves. The response is often some kind of intervention. You can’t do this, or rather you can’t do this — more, it isn’t done.

I think this theme of runaways in the series, and in American fiction generally, is incomplete without the corollary theme of intervention and the opposing figure of the rescuer. Often the show’s runaways are pursued by parental figures: Lane’s father, for example, who shames him at the end of his wooden cane into reconciling with his family in London. In the sixth season, Betty and Henry Francis take in a young violin prodigy who sets out on her own after a rejection from Juilliard. Betty pursues the girl to a run-down house in the city, but meets only other wayward youth and surrenders her search at a dead end. Toward the conclusion of the series, Roger’s spoiled daughter Margaret joins a hippie commune, abandoning her husband and young son, with the unanswerable justification that her parents had been effectively absent for most of her own childhood.

This theme of errant youth and parents who take up the crusade of returning them to order and responsibility recurs throughout midcentury fiction, including the genre movies and novels Don might have been reading. This was the decade of the French New Wave and the ascendance of Pauline Kael, of “trash” drifting toward the center of the culture. I can’t remember if we ever see Don reading one of Ross Macdonald’s Lew Archer novels, although the character was once played under the name Harper by Paul Newman who has a tiny “cameo” in season six’s “The Flood”. In the Archer stories, Macdonald uses the neutral perspective of his sardonic investigator — a “transparent eye” — to reveal tangled tapestries of plot, one square inch at a time.

Said plots were often inspired by Greek tragedy, Sophocles in particular, and the theme of parents’ sins visited upon their children. In the model of detective fiction provided by Oedipus Rex, the hero initiates an investigation which ultimately reveals a secret about his own history, a history that seals his downfall. Lew Archer’s clients are usually embroiled in a generational conflict, as in The Zebra-Striped Hearse, where a controlling father hires the detective to dig up dirt on his daughter’s fiancé. As in any good mystery, the real conflict emerges only after Archer prods and peels back several layers of deception and betrayal, finding a tragedy that engulfs both parent and child.

Writing through Archer, Macdonald’s voice maintained a sardonic if compassionate distance from the rescuers and runaways. Other writers of this generation erased the distance between themselves and their subjects. In Young Hearts Crying the poet Michael Davenport, one of the more direct authorial proxies employed by novelist Richard Yates, has the opportunity to save his nineteen-year-old daughter Lucy from a bad situation. After a period in which hints of Lucy’s flirtation with hippie subculture are parceled throughout the narration, Michael gets a call from his daughter in San Francisco, where she’s living in a bad neighborhood, may be pregnant, and is down to her last couple of dollars. He flies out immediately, picks her up and brings her back home, where a slow recovery can begin.

The details of this traumatic episode are so vague that one suspects, unlike other elements of Yates’ largely autobiographical fiction, the author has invented it without recourse to research or lived experience. (Referring back to the biography A Tragic Honesty, I can find no similar events attributed to Yates’ elder daughter Monica.) Young Hearts Crying stands out in the Yates corpus for its bifurcated perspective, switching from Michael’s story to that of his first wife Laura after their divorce in its second section, but the non-viewpoints characters often reflect prejudices that feel true to both Yates and his fictional counterpart. One of the most revealing passages occurs after Laura has been put to bed safely in the home Michael shares with his second wife Sarah, herself only a few years Laura’s senior:

He went out to get another drink, and barely made it back to the mantelpiece before he was crying. He turned quickly away and tried to hide it from her — no young wife should ever see an aging husband in tears — but it was too late.

“Michael? Are you crying?”

“Well, I didn’t get any sleep last night,” he said, covering his face with his fingers, “but the main thing is I’m proud of myself for the first time in — first time in years. Oh, Jesus, baby, she was all alone out there and she was lost — she was lost — and maybe I’ve never done anything right in my whole life, but son of a bitch I went out there and found her and got her and brought her home and now I’m fucking proud of myself, that’s all.” But he suspected even then that it wasn’t quite all, and that the rest of it couldn’t be told.

When he’d pulled himself together, apologizing, artificially laughing to prove he hadn’t really cried, allowing Sarah to lead him to their bedroom, he knew he had been reduced to tears by the final lines of “Coming Clean” — lines that had thrummed in the pressurized cabin of the plane today and now continued to roll and ring in his head — and by the knowledge that he’d written that poem when Laura was five years old.

The allusion in this excerpt to “Coming Clean” — the one great, long poem that Michael wrote early in his career and to which all his later work suffers in comparison, another proxy for Yates and his acclaimed debut Revolutionary Road — suggests how tragically, destructively entangled his perception of his own talent is with his self-image as a man who ought to be the champion, provider, and rescuer of the women in his life. (You can tell by the way “Coming Clean” recurs throughout the novel that Yates is as haunted by his early success as Michael is by his — attaching a holy significance to the alliterative title.) Michael is a deeply embarrassing character, impossible to respect because he at once insists upon the maintenance of old-fashioned norms he himself chafes against, and meanwhile hates himself for failing them. In an early passage, he inserts a cringeworthy reference to his brief prizefighting experience in a dust jacket blurb, as if to apologize for betraying his manhood with pretensions to artistry.

Through Yates and Macdonald and in their recurring incarnations throughout Mad Men, the rescuers receive a bruised sympathy. Divided against themselves, they appear as mirror versions of the runaways: desiring the freedom and possibility of youth, but restrained by their loyalty to orthodoxy, and driven by it to become bounty hunters on behalf of their own dubious values. In Mad Men the intergenerational theme gets a further burlesque treatment, one of Weiner’s favored devices (see various party scenes, like the lawnmower accident in “Guy Walks Into an Advertising Agency” that foreshadows both Dealey Plaza and the carnage of Vietnam, or Ken revealing the color of Allison’s underwear in “Nixon vs. Kennedy” to mirror the revelations of hidden selves in the A-plot). Pete, often depicted as a frustrated imitation of Don, becomes the caretaker for his senile mother, who believes herself to be living out a second youth with her sexually and motivationally ambiguous nurse Manolo.

In the show’s macro narrative, the agency Sterling Cooper (later SCDP and SC&P) itself becomes a runaway; a vessel for the reinventions, ambitions, and fantasies of its founding partners. Where Don, the arch-runaway, sometimes appears as a tempting devil figure within the series, his bogeyman Jim Hobart, head of McCann Erickson, is downright Mephistophelean. Hobart, who appears only in the first season attempting to lure Don away from Sterling Cooper before returning in the final episodes as their “big bad”, snatches independence away from the smaller agency by offering a lifeline revealed, in the end, as a constricting snare. “Stop struggling,” he says to the partners, interrupting Don’s pitch for Sterling Cooper West, yet another spinoff agency based in their Los Angeles office: one last run for the horizon.

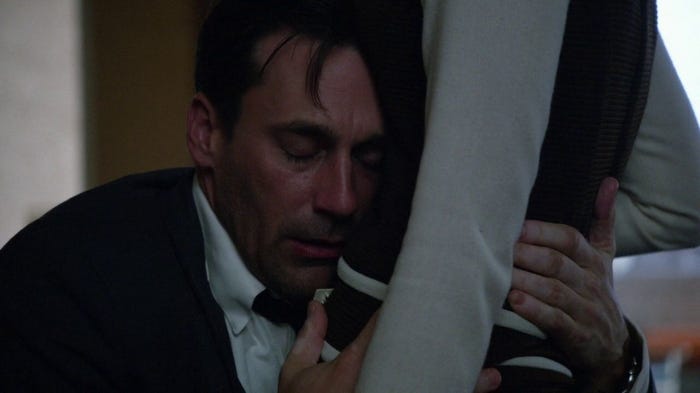

I can think of three major sequences that involve Don in pursuit of a younger quarry, each involving a woman and each of them taking place in the last three seasons, after Jon Hamm’s jawline has begun to recede into his neck and Don increasingly appears as an out-of-touch establishment figure. The first is the most freighted with potential violence, when he pursues his second wife Megan around their apartment after abandoning her in “Far Away Places”, like John Wayne charging after Natalie Wood in The Searchers. The second appears in “Favors”, when he tries to catch his daughter Sally before she can leave the building and reveal the compromising situation she’s found him in. Here, she gets away, and Don paces the lobby at a loss, having left his fate in the hands of his child.

The third chase unfolds in the antepenultimate hour of the series, “Lost Horizon”, as Don pursues his last fling, vanished ex-housewife Diana, to her old home in Wisconsin in hopes of turning up a clue to her whereabouts. Again his fist closes on thin air. He assumes a false identity to gain access to her ex-husband’s home. “You go by many names,” he once said to a perceived enemy. “I lost my daughter to God,” Diana’s ex-husband says, “and my wife to the Devil.” Here I also think about Don’s Sno-Ball pitch, and his devilish baritone: “This could change everything.”

Of course Lucifer was also famously unsatisfied with his job title — and “maybe Jesus was just trying to get the loaves and fishes account,” as Roger says. Elder generations seeking to restrain and punish the young is a theme as old as fiction itself, or at least Antigone. I like the framework of the rescuer because it captures something about the story the older generations want to tell about themselves, that they were once versions of the runaways but they eventually made the right, responsible choices, and by hook or by crook, so will their children. “Lost Horizon” ends with Don setting off for the coast again, in pursuit of no particular object, rescuer and runaway, on an odyssey at once romantic and disquieting. “What makes a man to wander?” asked the theme from The Searchers. That movie had an answer: nothing good.