The Power Broker, by Robert A. Caro

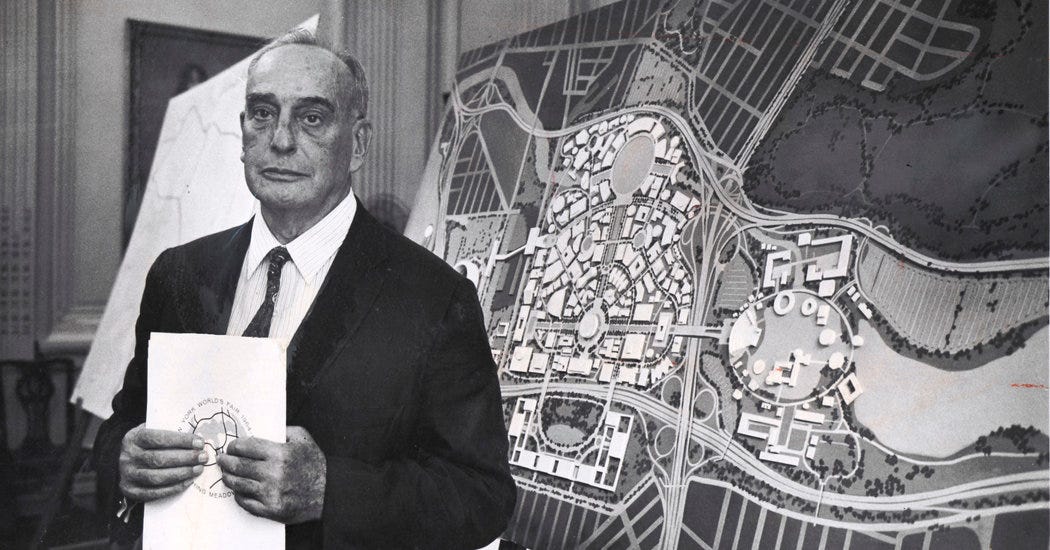

Robert Moses

I first encountered the work of Robert A. Caro when my dad picked up the fourth and most recent volume of his Years of Lyndon Johnson series, The Passage of Power. I read a little bit about Caro and his approach and decided to try the first book in the series, The Path to Power, for myself. I downloaded the audiobook, which is about forty hours long, and at first listened on long walks around the University of Georgia campus (this was when I was still living in Athens). Soon I had ordered a physical copy along with the rest of the books in the series, which I finished in a few months.

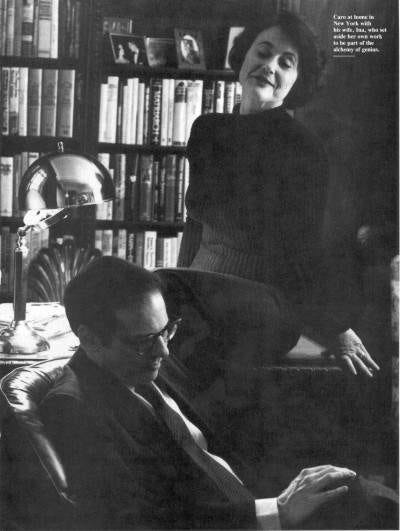

Caro’s meticulous research methods, long supported by the labor of his wife Ina Caro, are evident in the many passages of his work that trace a narrative gleaned mostly from archival materials. A particularly enlightening passage in The Path To Power uses handwritten notes from Johnson to piece together the flow of money from the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, as directed by Johnson, to candidates with whom he curried favor.

My favorite chapter in The Path to Power is “The Sad Irons”, which details the life of housewives in the Texas Hill Country where Johnson grew up. Caro writes at length about the back-breaking labor involved in the chores these women carried out daily in order to establish what a difference it made when Johnson used his influence to get electricity run to the Hill Country for the first time. Part of Caro’s appeal is his expansive vision of history, but in his philosophy this never means straying from the book’s subject. Having said many times over the years, and written it into the title of his books, that his central subject is power, a chapter such as “The Sad Irons” works as an extension of this project. Johnson’s power was not merely his own, it worked in and left lasting effects on the world around him. The legacies of power and its use are also at the heart of Caro’s first biography, The Power Broker.

The subject of The Power Broker, Robert Moses, was best known as the first Commissioner of the New York City Department of Parks, which was formed at his initiative after his term as the President of the Long Island State Park Commission. Later Moses would take the Chairmanship of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, a post he held until 1968, although he thereafter referred to himself as “Coordinator” and used that title in all his correspondence. Moses was responsible for the building of many of New York City’s public parks, including the Jones Beach facilities on Long Island, as well as bridges, tunnels, and expressways. He never held elected office yet remained a dominant force in New York City politics for four decades.

Alec Baldwin plays a powerful city planner named Moses Randolph in Motherless Brooklyn (2019)

Due to his control of public funds and his popularity with the general public, although Moses was not an elected official, for decades no Mayor or Governor found it possible to remove him from power or even reduce the number of positions he held. In fact, since Moses built projects so quickly and acted so decisively, executives were eager to stay in his good graces and draw from his political capital. Caro writes that when there were not enough parks or expressways opening, Moses would hold ceremonies opening sections of expressways, to provide more photo ops and ribbon-cutting ceremonies that could be ammunition for a Mayor’s re-election campaign.

Throughout the book Caro repeats a quotation from Ralph Waldo Emerson: “An institution is the lengthened shadow of one man.” He first uses this specifically to refer to the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, which became the chief vessel for Moses’ power, as he used it to amass billions of dollars in buying power through bond issues and investments, which then became political leverage which cemented his position beyond any public accountability. The Emerson quotation comes to stand in for the entire city, which Moses engineers to his preferences beyond any protest or reasonable counterargument.

The book documents the explicit and implicit racism of Moses’ policies. Numerous sources say on the record that Moses’ prejudice against African-Americans was common knowledge; Moses built hundreds of parks throughout the city but only one in Harlem; he consistently favored car travel and suppressed public transportation used by poor and minority residents. One of the book’s most compelling chapters, “One Mile”, which was reprinted in The New Yorker on publication, details how the Cross-Bronx Expressway route effectively destroyed the racially integrated East Tremont neighborhood. Residents proposed an alternate route to save their homes, a route that would have required fewer relocations and would have saved the Expressway money, but even after a public hearing Moses refused, for reasons that remain opaque.

At a certain point in the book, Moses’ opposition to public transportation becomes maddening beyond the fact of its prejudicial origin. While car culture was still developing in the 1930s, the Triborough Bridge Authority operated under the assumption that the three spans of the bridge would ease traffic on the East River and Queensborough spans by 40-50%. Instead traffic on the Triborough exceeded all estimates and congestion rapidly worsened on the East River spans. Rather than rethinking the theory of congestion Moses and the Authority moved to build more bridges, always with the stated goal of reducing congestion and compounding it with each opening. Overpasses were built below the level of clearance that would have allowed city buses to pass underneath, restricting the routes they could use. Perhaps most egregious of all was Moses’ refusal to build expressways with allowance for high-speed rail to travel in the middle. Although Moses controlled the necessary funds through the public authorities to improve mass transit in New York City, he not only refused to allocate them accordingly but built his expressways in such a way that rail lines would be many times more costly and difficult to build in the future, effectively sealing in his policies of car commuting and and brutal congestion for decades.

Robert and Ina Caro

The question of how Moses will eventually be removed from power drives the book’s suspense. Caro, who has a fondness for rhythmic and rhetorical flourishes such as one-sentence paragraphs to emphasize a point, says that only Moses could have lost himself power. This is both true and not; while Moses’ hubris created many possible weak points for attack, for many years the attacks were ineffective. A pair of chapters about two late-career scandals that mobilized white liberals against him, and fractured the loyalty to Moses long held by The New York Times’ Iphigene Sulzberger, suggest that these episodes created an opening for reporters such as Gene Gleason and Fred Cook of the New York World-Telegram to write investigative stories about Moses. One scandal involved a parking lot for the Tavern on the Green restaurant for which a corner of Central Park, considered sacred ground by city residents, would be torn up; the other involved Shakespeare in the Park, ironically an initiative Moses personally supported yet found himself opposing when a zealously anti-Communist Parks executive refused to allow future performances. These chapters suggest that while Moses had done plenty to make himself unpopular with poorer residents over the years, he never lost popularity in the press (where he was always the man who Got Things Done) and thus with the city at large until he became an enemy of affluent white liberals.

Moses did resign many of his positions after these scandals, although Caro omits a key figure in Moses’ declining influence: activist Jane Jacobs, who helped turn public opinion against the Lower Manhattan and Mid-Manhattan Expressways. Although there is literally no mention of Jacobs in the book at all, journalist Norman Oder wrote and received a response from Ina Caro confirming that there had indeed been a Jane Jacobs chapter in the original manuscript, which was so long — over a million words — that it had to be cut down by a third to meet the limit for print publication. That The Power Broker was condensed from an even longer manuscript helps to understand the often episodic nature of Caro’s writing, which does not attempt to draw a consistent narrative line beyond his understanding of Moses’ character and often devotes single chapters to side characters, such as Moses’ estranged brother Paul, who are not spoken of elsewhere.

Ultimately, though, bad press alone could not remove Moses from power, and his final enemy arrives in the form of the concentrated wealth of Governor Nelson Rockefeller. In the aftermath of Moses’ dismal handling of the 1964 World’s Fair, his popularity had ebbed to the point that a confident enemy could move against him. Rockefeller, whose incomparable personal wealth made him a match for Moses’ political influence, had a key ally in his brother David, the head of Chase Bank, which coincidentally was the largest holder of Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority bonds. This enabled Rockefeller to merge the TBTA into a new Metropolitan Transit Authority, where he declined to appoint Moses as Chairman, effectively ending Moses’ period of public influence in 1968. Without this particular confluence of circumstances — a super-wealthy Governor insulated from Moses’ political meddling and independently allied with TBTA’s largest bondholder — it’s uncertain whether another executive could have capitalized on Moses’ waning influence to remove him from power so decisively.

Moses with Nelson Rockefeller

Caro’s book does what the best books do: it makes one look at the world in a different way. Someone reading this book in New York City might look differently at the bridges and parks they pass by every day, reflecting on Moses’s means of planning and building them, and what they might have replaced. They might look at the lakefront now separated from the city by a highway, and think about Caro’s evocation of a land lost to future generations that cannot be recovered. Someone not in New York City might look at their own surroundings and be moved to research how a park, a bridge, or a road was planned, built, and paid for. They might look into what it replaced, or what it crowded out.

Most of all the book is revelatory about political realities and the horizons of our political vision. What Caro communicates with his meticulous research and his literacy in financial data, in engineering and development, is the idea that the world as it is exists because someone once decided to make it that way. His illustration is vivid because he joins this idea to the will and imagination of one man: Robert Moses, or even Lyndon B. Johnson in his volumes on the President. His identification with these characters gives his writing its propulsive, addicting qualities. But he also details that Moses did not act only on his imagination, and consciously or not he identified and allied himself with certain interests, or with a certain class and race of people. Similarly, Johnson’s feats of legislation were not sole accomplishments. But they only came about because someone took action.

Moses has a legacy of stone, concrete, and steel, elements as tangible and seemingly immovable as the natural world. To younger generations they seem pre-ordained and inalterable. For most effects and purposes, they are. Moses built an awful cruelty and indifference into New York City, one that told poor residents that they were not wanted, that reminded black children of the inexplicable coldness their city bore them every time they walked the streets of Harlem. To those children this cruelty must have seemed a fact of life, a natural law that could not be amended. With The Power Broker, Caro illustrates that this world we live in was not an accident, but a choice. His book suggests that it might be possible to choose a different one.